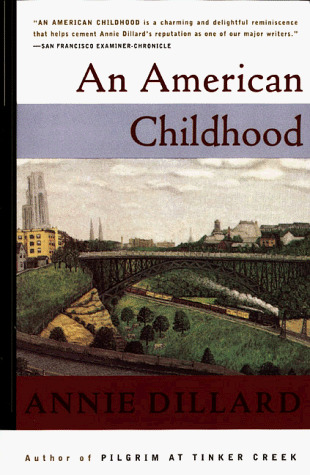

Today I finished Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood, a book I enjoyed a lot, and yet felt like it could have been more. I kept expecting the memoir to open up, from an exuberant description of her idyllic childhood, to a more general reflection on the world in which she grew up and her place in it. But that never really takes place, except in passing here and there (for example when she suggests her father’s trickle-down theory of economics might not be quite right).

Instead, Dillard’s memoir remains absorbed in the bliss of detail, in the escape from self which is total concentration. Dillard herself outlines a kind of philosophy throughout the memoir based on this total immersion into an interest or a pursuit. A part of me is attracted to this philosophy, as I’ve mentioned before in a post about Thoreau’s Walden (who, by the way, is on the extreme opposite end of the detail-big picture thinking spectrum from Dillard).

As attractive as this philosophy is, I wonder if it is wholly compatible with one of the things I admire most in writing: Don’t great books on some level subordinate description to the overall thematic development? Just comparing Dillard to other memoirists I’ve read recently, I would say her point of view evolves much less over the course of the memoir than does say Anand Prahlad’s in The Secret Life of a Black Aspie.

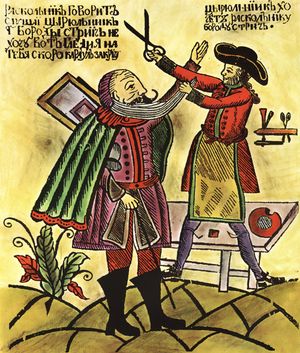

If I had to compare Dillard to another writers in this respect, I would say she reminds me of two Russian writers: Maxim Gorky’s Childhood, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. Gorky was of course an incomparable raconteur with a legendary memory for detail and character, but his stories seem to progress mostly horizontally, rather than through a vertical accumulation to a chord. His style was melodic rather than symphonic. Nabokov, very much like Dillard, seems to have resolutely refused to approach anything so messy as culture in a collective sense, preferring to raise the observations and memory of an individual consciousness to the supreme heights of his aesthetics. (Nabokov and Dillard were also both naturalists and the products of a very select and privileged upbringing).

It seems to me a different kinds of mind are at work here, and I wonder about the application of theories of neurodiversity to literature. There seem to be more detail-oriented writers, who eschew the political and the collective, seeking to forget the self in pure concentration, and then there are the more socially conscious writers, consciously seeking the self through belonging in a community. Although in many ways I sympathize with the first group, and the basic principle of neurodiversity implies that we shouldn’t prioritize one mode of thinking and writing over another, when it comes to what I consider great writing, I tend to lean a little bit towards the second group.