Beech Blight Aphids

Beech blight aphids are funny little insects that feed on the sap of beech trees. They have fluffy white appendages (I’m not sure what to call them) which they wag back and forth in a kind of dance. Apparently this is a defensive mechanism, although to me this would seem to just draw attention to them (but I’m not the predator they’re worried about). You can watch a video of the dance here.

These aphids are visible from a good distance because one, it looks like snow has fallen on one particular beech limb, or a thoughtful do-gooder has knitted a one-armed version of one of those sweaters for trees, and two, because they tend to leave what appears to be a patch of charred earth underneath them.

Beech blight aphids excrete a honeydew which is itself the food for a mold fungus called Scorias spongiosa previously featured on this blog.

On the whole, beech blight aphids and their associated fungus are relatively harmless to beech trees. The most damage they will do is cause the die-back of a twig or two.

Dog Vomit Slime Mold

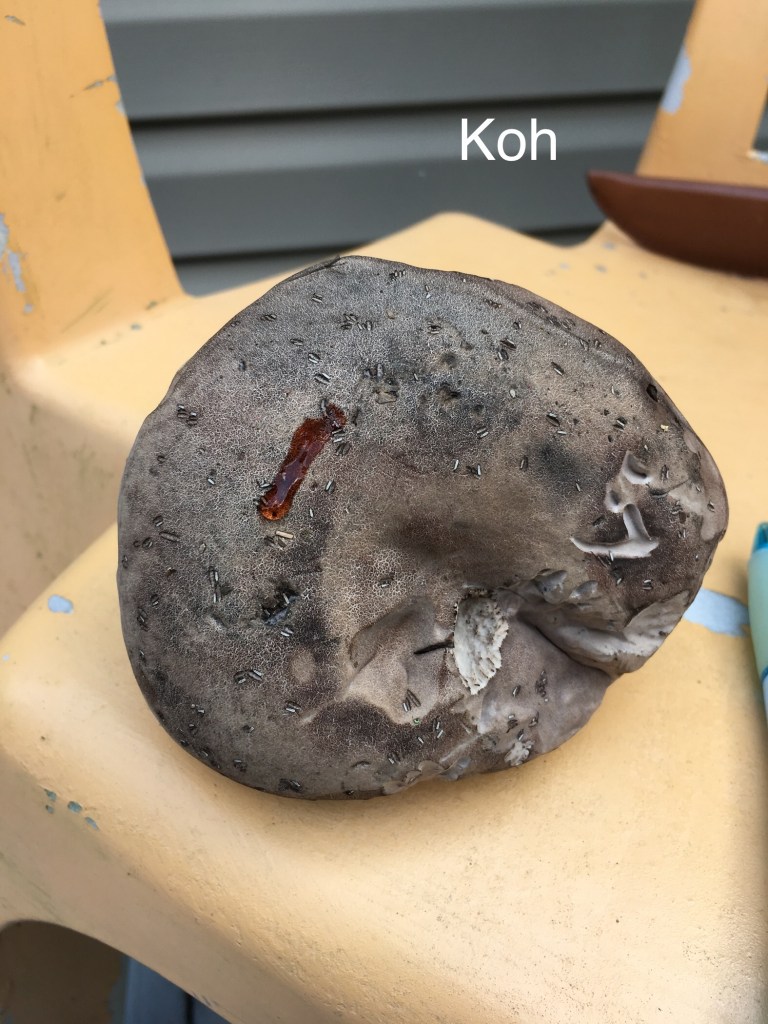

Fuligo septica is one of the largest and most commonly encountered slime molds. Slime molds are not fungi (I’m staying true to the title of this post), a key difference being that slime molds are basically big multinucleated aggregations of undifferentiated cells (whereas fungi are truly multicellular organisms with differentiated cell types).

Fuligo septica is more commonly called “Dog Vomit Slime Mold” or “Scrambled Egg Slime Mold” and is fairly common in wet urban mulch. As it matures it darkens and dries out, releasing spores in the wind.

Genus Monotropa

I won’t say too much about these guys because I’ve written about them before. But I’ve found some especially prominent and colorful specimens recently I thought I would share.