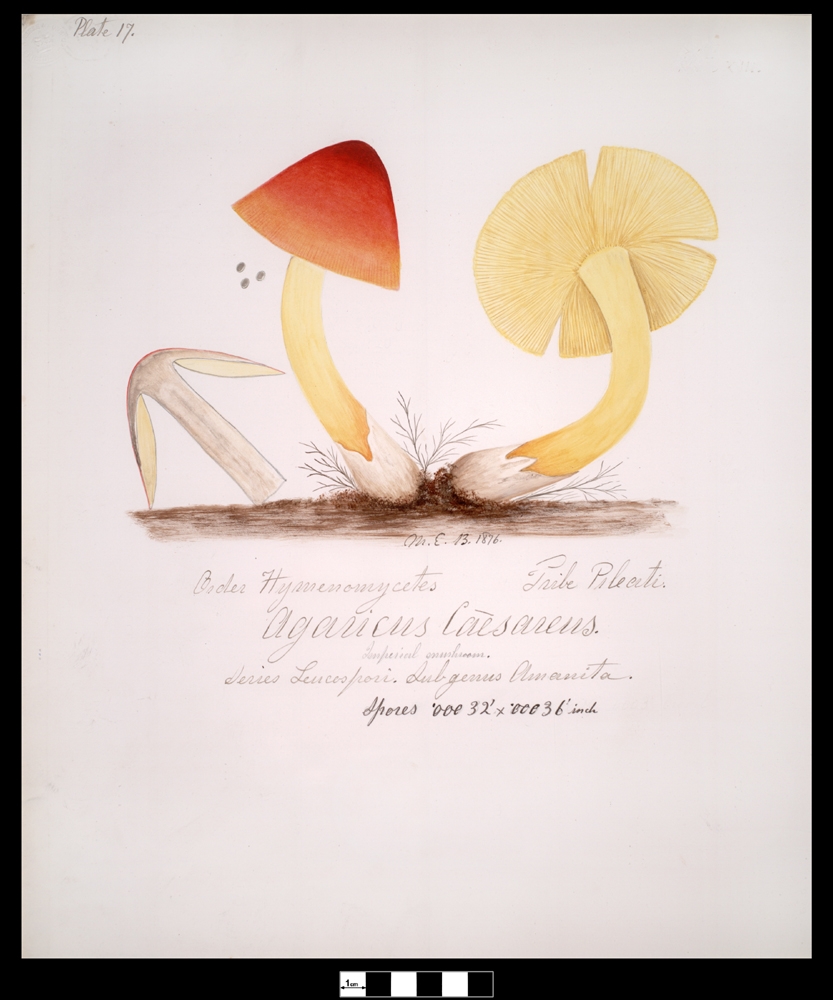

Amanita banningiana, or Mary Banning’s Slender Caesar, is a common summer mushroom, and one of the few dozen Amanitas distinctive enough to be identified by sight. It belongs to the section Caesarea, so named because the European type species Amanita caesarea featured in Roman cuisine.1

What tends to set this section apart from other Amanitas is the sack-like, “saccate” to be technical, volva at the base. These mushrooms look like they are emerging from an egg. They also tend to have yellow-tinted stems and gills, and no patches on their cap. The patches on other Amanita mushrooms (such as the fly agaric) are kind of like egg-shells from the shattered universal veil. But in the case of Caesar mushrooms the veil remains relatively intact at the base of the mushroom so there are no patches on the cap.

What is really interesting about this mushroom though, is the story behind its name. Mary Elizabeth Banning was an early American mycologist and illustrator, known for The Fungi of Maryland, a manuscript containing 174 watercolor illustrations of local fungi. Had it been published, it would have been an enormous leap forward for the American mycology of the time, but unfortunately it sat in a drawer for 91 years after her death, only to be unearthed in 1981.

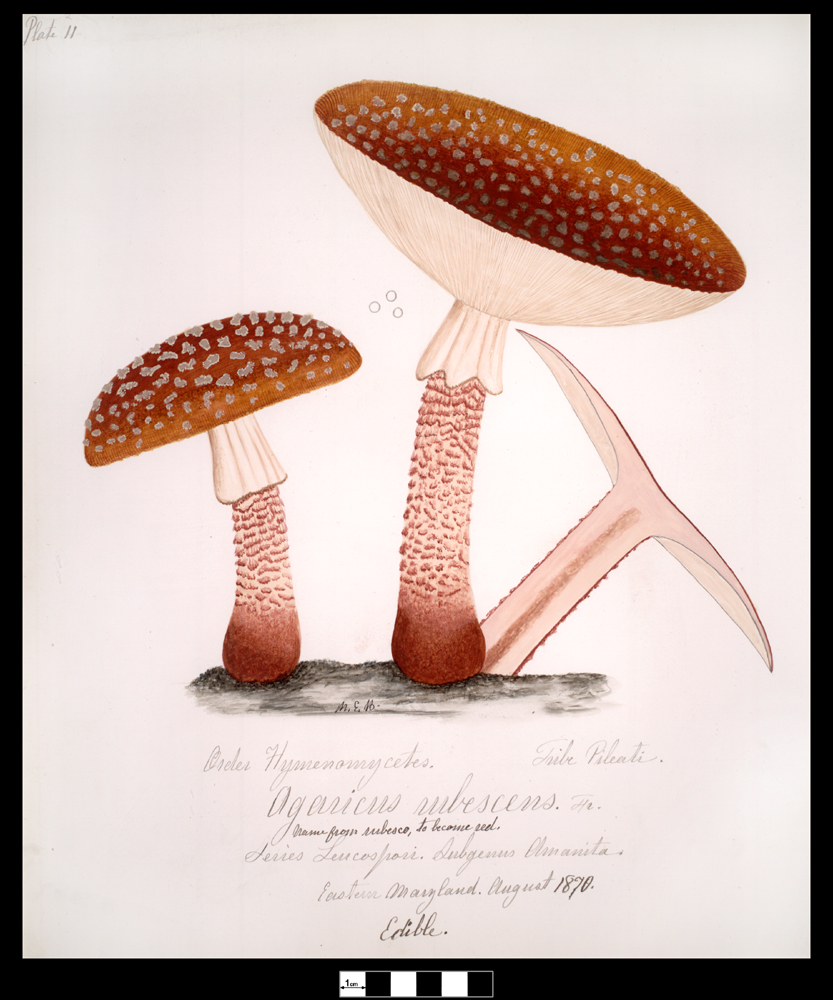

Mary Elizabeth Banning was the first to describe what is now called Amanita banningiana, but she did not consider it its own species. Rather she described it as a variant of the European Amanita caesarea mentioned above. You can compare her watercolor illustration above with the photographs below.

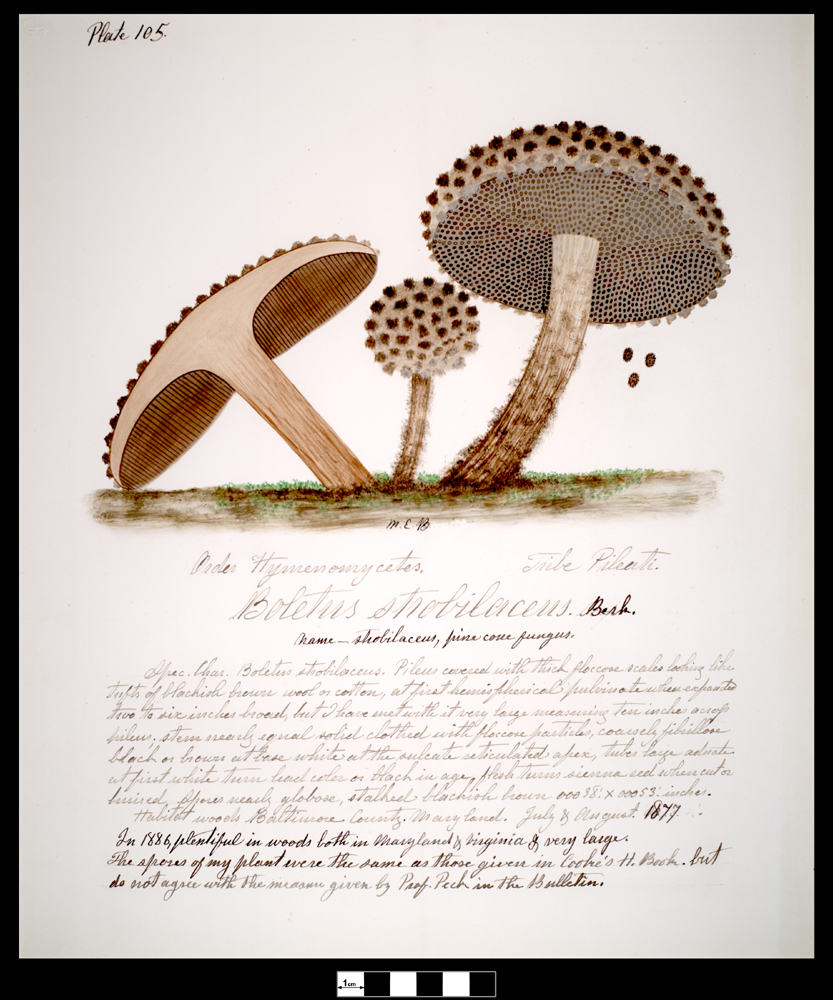

I wish more was known about her life. We know that after her father died (when she was 23) she was responsible for taking care of her mother and chronically ill sister, and that hiking became a release from the stultifying atmosphere of home. We know that although The Fungi of Maryland was never published, she did publish several papers in the Botanical Gazette of the 1880s in which she described 23 previously unknown fungi, and that despite this, and being probably the foremost expert in her region, she faced considerable skepticism and hostility from the scientific establishment of the day. Though by the time she died she was virtually penniless, she came from “an elite plantation family,” which probably at least partially explains how she was able to devote herself to science despite zero financial support from the scientific community. For the most thorough treatment of her life see: Mary Elizabeth Banning , MSA SC 3520-13591 (maryland.gov)

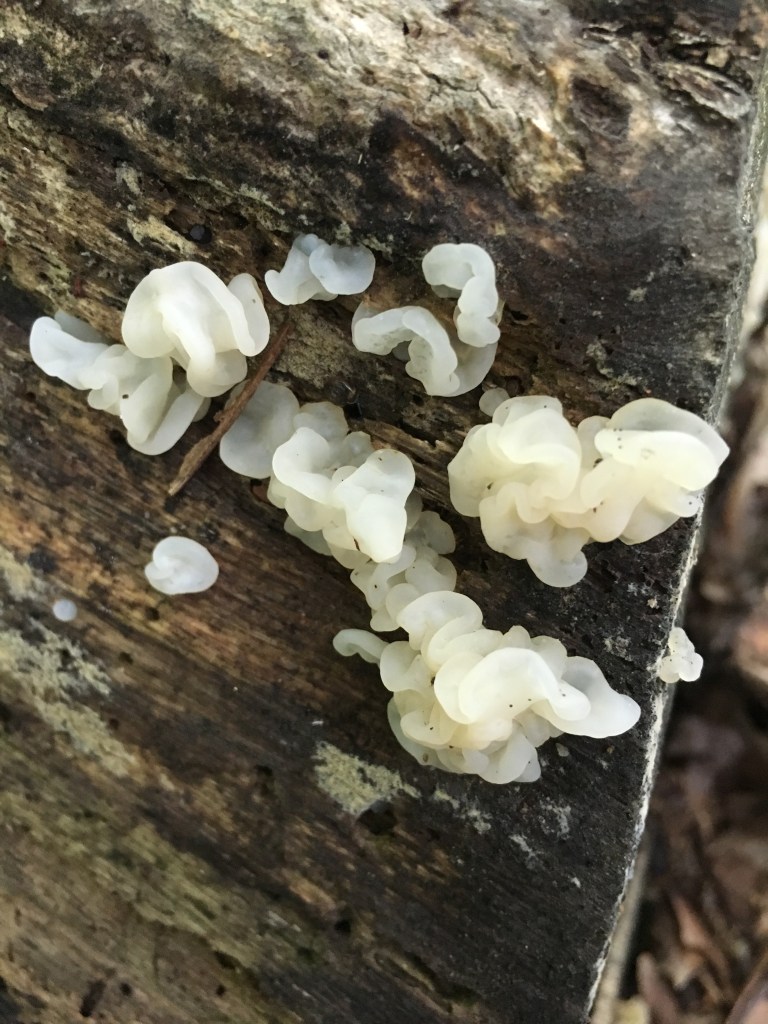

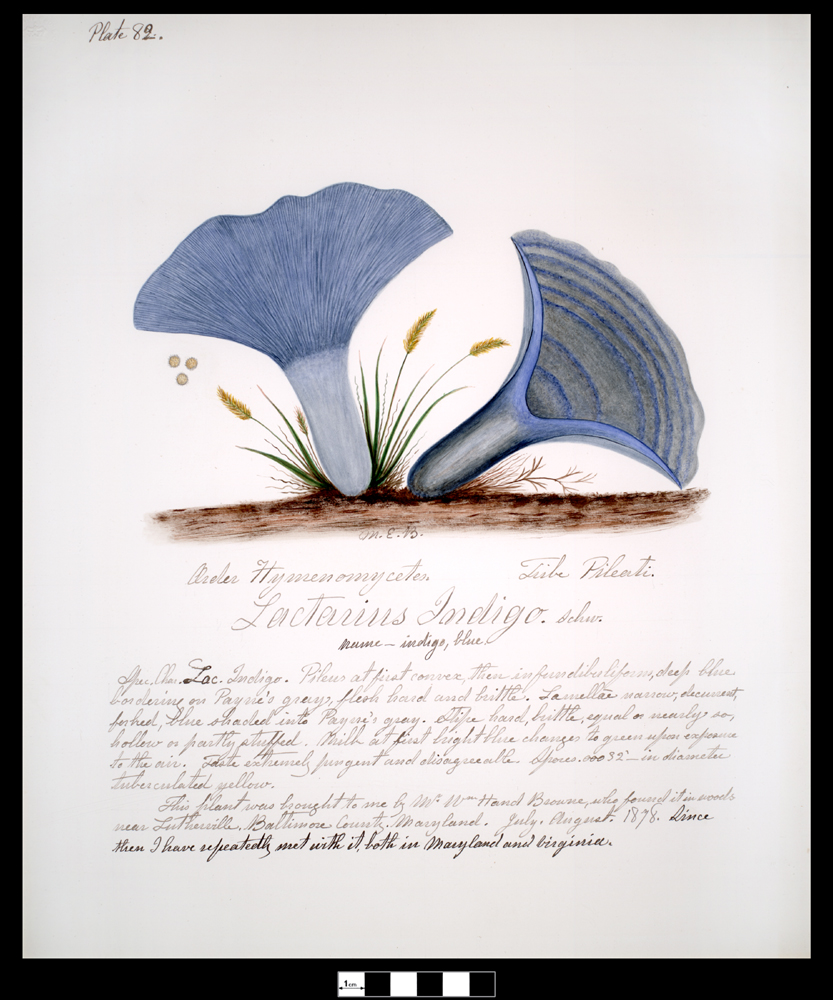

Below are several more of her illustrations (available online here) paired with photos I’ve taken of the same mushrooms. As someone who photographs mushrooms, I find it very interesting to compare the sometimes unintended insights of photography with the more conscious creations of the illustrator.

To have been an early American mycologist must have been an exhilarating and simultaneously despairing experience. Fungi are bewildering even today with technologies such as gene sequencing, photography, widely available field guides, and online resources like iNat and Mushroom Observer. The early American mycologists, by contrast, had next to nothing to go by. Which might also have made things less confusing…

Perhaps because there was no greater authority than their own firsthand experience, that firsthand experience had a greater reality, a sense not only of observing, but of creating. On the other hand, help was close to non-existent, at least in your immediate surroundings. Such was the case for Mary Elizabeth Banning, who corresponded for 30 years with Charles Peck (the so-called “Dean of American Mycologists”) but never met him. At the time she was working, there was no widely available illustrated guide to American fungi1. Perhaps this helped her to see the world with her own eyes, but it must have also been very discouraging work.

For more information/sources see: