Given that the unemployment rate for people with disabilities is more than twice that of people without disabilities (7.3% vs 3.5% in 2019) there are two major explanations. One, people with disabilities lack the essential skills to gain employment, and two, workplaces are not accessible to people with disabilities (remember that unemployment rates only consider people who are actively looking for jobs, so the explanation that fewer people with disabilities are looking for jobs is not relevant). For the most part, our public policy assumes the first explanation. It sees the problem as lying in something disabled people lack, and therefore sees rehabilitation as the main solution.

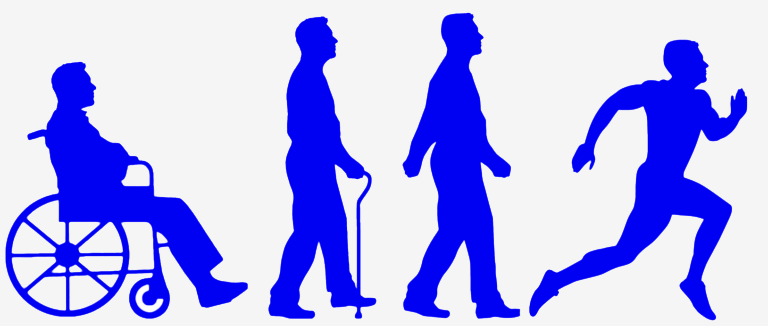

At first glance, this is pretty reasonable. But it places the responsibility for their own underemployment on people with disabilities. There is a long-standing assumption manifest in the image above (taken from a website for a physical therapy provider: https://integratedmedical.care/bucks-county-physical-therapy/) that disability is backward, a problem to be overcome, an obstacle to progress. The implication is that people with disabilities have a civic duty to undergo rehabilitation and become as able-bodied as they possibly can. Similarly, the assumption that people with disabilities are underemployed because they lack skills (perhaps social, cognitive or emotional) puts the onus on them to undergo various correctional therapies.

Teaching someone a skill is not necessarily forcing them to reject their disability. For example, teaching someone with autism social skills is not necessarily teaching them to become “less autistic,” it is just teaching them to live better with their autism. Of course the problem arises when it is the provider who decides what a “better” life looks like. Hard as it may be to imagine, some people with ADHD, for example, may not want to improve their executive function, as providers tend to assume they do. Rehabilitation assumes disabled people have an obligation to overcome their disabilities, but this creates a double standard (people without disabilities are not required to “overcome” themselves).

What if the problem is not with people with disabilities, but with workplaces? In some cases it is not so hard to see ways workplaces could be made more accessible (using task separation, time management apps that provide prompts, wall calendars, etc… for the ADHD example above). But do “reasonable” accommodations exist for every possible disability, and even when they do exist are they fully effective? Is it realistic to expect businesses to drastically adapt their way of doing business in the interests of diversity? And can neurodiverse businesses survive in a free market economy? For the economy to become truly accessible would require a huge change in our country’s priorities, what we value as “work,” and in the narratives we tell ourselves about disability (and narratives are no easy thing to change).

So we have an eternal balancing act to perform. On the one hand, people with disabilities shouldn’t be placed in a double standard, where they are responsible for compensating for their perceived deficits. On the other hand, society is not going to change overnight, and so in the meantime people with disabilities will have to learn to adapt if they want to participate in the workforce, unfair as that is. Just like people of color, who have to work twice as hard to obtain the same ends, people with disabilities are expected to undergo lengthy “interventions,” therapies, and “rehabilitation,” in order to have the same chances as their non-disabled peers. Funding programs to provide these interventions (assuming they are voluntary—which is a tricky question) is thus unideal, but perhaps, necessary.

Maybe more on this later.