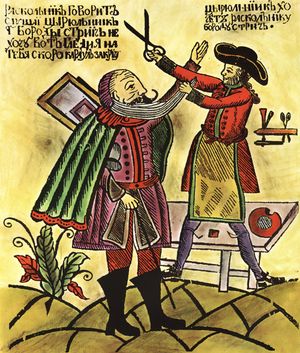

One of the most striking things about the reign of Peter the Great is how much he was able to get away with as a ruler. I mean not in terms of his personal life, but in terms of his demands on the people as ruler of the State. Over the course of his reign, everyone, at all levels of Russian society from serfs, to priests, to boyars, gave up ground as individuals for the benefit of the State, in the person of one man: Peter. It’s hard to convey the enormity of the changes Peter enacted. For that, you’ll have to read Massie’s 900 page biography, but I’ll try to mention a few of the more memorable. To start with, he banned beards.

He taxed the people literally to death (a government monopoly on salt, for example, made it so it expensive peasants who couldn’t afford it often “sickened and died,” I assume from the inability to preserve food!?). He introduced the tax on “souls” you may be familiar with from Gogol’s Dead Souls. He ended the semi-autonomy of the Orthodox Church, making it effectively a Ministry of the State. To quote Massie, “For the next two centuries, until 1918, the Russian Orthodox Church was governed by the principles set down in the Ecclesiastical Regulation. The church ceased to be an institution independent of government; its administration, through the office of the Holy Synod, became a function of the State.” Nor was all that he took from the Russian people then reinvested back into Russian society, in the form of schools or some other such enlightened institution. Rather, as in 1710, he spent 80% of State revenue on the army and navy.

The list could go on and on. Peter’s whole reign is stamped with two words: State Power. How was he able to accomplish this? Conventional wisdom tells us that people deeply resist change. Most of us assume that any alternation to our present collective reality would be met with the enormous resistance of the status quo. We have a cognitive bias in favor of stability, and yet there are historical examples, as recent as Covid-19, of huge societies shifting in a matter of weeks or months.

But Peter’s “reforms” are still more interesting because—at least according Massie—they did not stem from the great mass of people, but from one man. Peter the Great seems like the incarnate refutation of Tolstoy’s theory, advanced in War and Peace, that it is not the leaders who control society, but the great mass of people who control the leaders. After all, as Tolstoy points out, isn’t it absurd that the will of one whimsical man could be sufficient to uproot or end tens of thousands of lives? Why would people go along with such an absurd system? Why would thousands of powerful landowners consent to have their beards shorn, their serfs taxed, and the independence of their church abolished, rather than just gang up on one man and throw him in the river?

Unfortunately, I’m no Foucault. I’d have to read much more deeply into Russian history to really understand why Peter was able to do what he did. But a couple ideas come to mind. Maybe “freedom” is not so innately precious to mankind as we assume. Maybe instead of assuming that individuals behave like Newtonian particles according to rational laws of force and inertia, we need to look at political power as the product of certain cognitive biases, as Richard Thaler has done in the field of Economics. Perhaps an even more subtle historian that Massie will come along and demonstrate that Peter’s reforms didn’t “stem” from the top after all, but from an infinitude of invisible causes permeating the whole system, just as Tolstoy thought. But still, we would have to throw out the assumption that people always act for their own individual benefit unless compelled to do otherwise.

You might enjoy listening to the Revolutions Podcast (https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/). He covers leftist revolutions across history. He’s currently doing a really deep dive into the Russian Revolution which covers Peter the Great and some of the early Russian leaders. Really great stuff!

LikeLike

Thanks for the tip, I’ll check it out!

LikeLike